Quick question: If something has been healing millions of people for thousands of years, is it an alternative treatment?

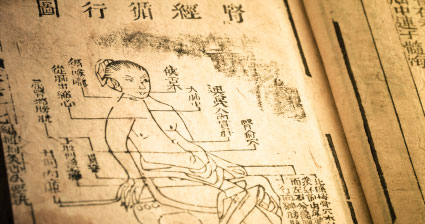

While relatively new to the west, the practice of acupuncture is one of the oldest medical practices, and has been healing people for a recorded 2,000 years, with some authorities dating it back 4,000 or 5,000 years.

The track record spanning millennia, however, is not always enough to encourage those unfamiliar with it to even experiment with acupuncture. This is unfortunate because the list of conditions that can be treated by or improved with acupuncture is surprisingly extensive. Fortunately, more and more Western physicians are embracing the practice and referring their patients to acupuncture as part of their overall treatment plan.

Side-Effects?

Acupuncture falls under the heading of what is commonly referred to as Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). The focal point for treatment has to do with the body’s vital energy, or Qi (pronounced chi), and circulation. When energy in the body is unbalanced we can get sick or become fatigued. Rather than putting something into the body or removing it, the aim of acupuncture is to regulate, or balance, this energy within the body.

If all this “energy” talk sounds a bit woo-woo, you may be comforted by the fact that there are almost no unwanted side effects and few who won’t benefit from it. It is very difficult to harm with this essentially gentle medicine. Side effects that do come up are all in the plus column, such as better sleep, more energy, better digestion, and reduced stress. The stress reduction can come as a surprise, as many don’t even realize that “stressed” is their norm.

The most common concern with acupuncture is pain associated with the needles. In general, however, we all experience far more tortuous and painful treatments elsewhere. It may be helpful to know that the needles are more like filaments and are inserted superficially.

A licensed acupuncturist will give a thorough intake and know what is contraindicated for each patient. They will ask about pacemakers, implants, replacement devices in your body, as well as any medications and conditions. They are trained to tune into all of these and make accommodations. While many very skilled health practitioners add acupuncture to their treatment options, a licensed acupuncturist has approximately 3,000 hours of training and a masters level degree of training in an authentic eastern medical model.

After an assessment, needles are inserted at particular spots that correlate with “stagnation” in the body as diagnosed by the acupuncturist. Communication is paramount in treatments, and patients are encouraged to speak up if they are uncomfortable in any way. After the needles are placed, patients are left to relax for what many refer to as a “healing nap,” which is usually a seemingly short 15 to 30 minutes.

Why see an acupuncturist?

Pain management is one of most common reasons to see an acupuncturist, and is also one of the most responsive conditions to the practice. For some the very first treatment is all but a miracle in relief, while others need a few treatments to see results. It is recommended to have two to three treatments before deciding if you are benefiting from them. Some practitioners will suggest a few treatments close together in the beginning to assess improvement.

As well as pain management, there are myriad conditions that respond well to acupuncture. Under the heading of neurological complaints that improve are headaches, neuralgia, stroke residuals, vertigo, and Multiple Sclerosis. Musculo-skeletal improvements include Arthritis, trauma or injury, Sciatica, and Fibromyalgia.

Allergies and other issues associated with repertory function often improve with treatment, as do many eye, ear and dental conditions. Many find acupuncture highly effective in the arena of women’s health, including infertility and reducing the symptoms of menopause. In fact, in Asian cultures, where acupuncture is common, women experience far fewer “symptoms” of menopause.

For some, their acupuncturist is their primary care physician, while many others simply include the practice as part of their overall approach to wellness. Because of the regulating nature of treatments, scheduling them monthly or quarterly can head off any number of complaints.

Take-away for the week: There is nothing to lose with acupuncture, and much that can be gained. The worst-case scenario is a lack of immediate results.

Recovering substance abusers don’t have to languish in pain. In fact, most can successfully utilize a number of non-opioid pain treatment therapies.

Recovering substance abusers don’t have to languish in pain. In fact, most can successfully utilize a number of non-opioid pain treatment therapies.